This post was originally published on this site

Ask Google or Siri: “What is Taiwan?”

“A state”, they will answer, “in East Asia”.

But earlier in September, it would have been a “province in the People’s Republic of China”.

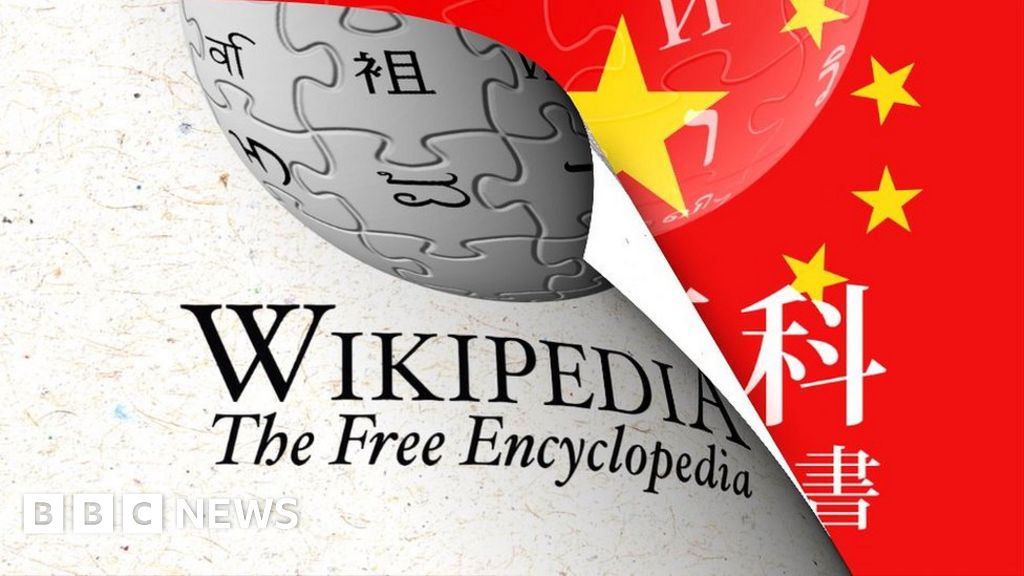

For questions of fact, many search engines, digital assistants and phones all point to one place: Wikipedia. And Wikipedia had suddenly changed.

The edit was reversed, but soon made again. And again. It became an editorial tug of war that – as far as the encyclopedia was concerned – caused the state of Taiwan to constantly blink in and out of existence over the course of a single day.

“This year is a very crazy year,” sighed Jamie Lin, a board member of Wikimedia Taiwan.

“A lot of Taiwanese Wikipedians have been attacked.”

Edit wars

Wikipedia is a movement as much as a website.

Anyone can write or edit entries on Wikipedia, and in almost every country on Earth, communities of “Wikipedians” exist to protect and contribute to it. The largest collection of human knowledge ever amassed, available to everyone online for free, it is arguably the greatest achievement of the digital age. But in the eyes of Lin and her colleagues, it is now under attack.

The edit war over Taiwan was only one of a number that had broken out across Wikipedia’s vast, multi-lingual expanse of entries. The Hong Kong protests page had seen 65 changes in the space of a day – largely over questions of language. Were they protesters? Or rioters?

The English entry for the Senkaku islands said they were “islands in East Asia”, but earlier this year the Mandarin equivalent had been changed to add “China’s inherent territory”.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests were changed in Mandarin to describe them as “the June 4th incident” to “quell the counter-revolutionary riots”. On the English version, the Dalai Lama is a Tibetan refugee. In Mandarin, he is a Chinese exile.

Angry differences of opinion happen all the time on Wikipedia. But to Ms Lin, this was different.

“It’s control by the [Chinese] Government” she continued. “That’s very terrible.”

‘Socialist values’

BBC Click’s investigation has found almost 1,600 tendentious edits across 22 politically sensitive articles. We cannot verify who made each of these edits, why, or whether they reflect a more widespread practice. However, there are indications that they are not all necessarily organic, nor random.

Both an official and academics from within China have begun to call for both their government and citizens to systematically correct what they argue are serious anti-Chinese biases endemic across Wikipedia. One paper is called Opportunities And Challenges Of China’s Foreign Communication in the Wikipedia, and was published in the Journal of Social Sciences this year.

In it, the academics Li-hao Gan and Bin-Ting Weng argue that “due to the influence by foreign media, Wikipedia entries have a large number of prejudiced words against the Chinese government”.

They continue: “We must develop a targeted external communication strategy, which includes not only rebuilding a set of external communication discourse systems, but also cultivating influential editors on the wiki platform.”

They end with a call to action.

“China urgently needs to encourage and train Chinese netizens to become Wikipedia platform opinion leaders and administrators… [who] can adhere to socialist values and form some core editorial teams.”

Shifting perceptions

Another is written by Jie Ding, an official from the China International Publishing Group, an organisation controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. It argues that “there is a lack of systematic ordering and maintenance of contents about China’s major political discourse on Wikipedia”.

It too urges the importance to “reflect our voices and opinions in the entry, so as to objectively and truly reflect the influence of Chinese path and Chinese thoughts on other countries and history”.

“‘Telling China’s story’ is a concept that has gained huge traction over the past couple of years,” Lokman Tsui, an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told BBC Click. “They think that a lot of the perceptions people have of China abroad are really misunderstandings.”

To Tsui, an important shift is now happening as China mobilises its system of domestic online control to now extend beyond its borders to confront the perceived misconceptions that exist there. Wikipedia has confronted the problem of vandalism since its beginning. You can see all the edits that are made, vandalism can be rolled back in a second, pages can be locked, and the site is patrolled by a combination of bots and editors.

People have tried to manipulate Wikipedia from the very beginning, and others have worked to stop them for just as long.

However, much of the activity that Lin described isn’t quite vandalism. Some – such as Taiwan’s sovereignty – is about asserting one disputed claim above others. Others, subtler still, are about the pruning of language, especially in Mandarin, to make a political point.

Should the Hong Kong protests be considered “against” China? Should you call a community “Taiwanese people of Han descent”, or “a subgroup of Han Chinese, native to Taiwan”?

It is over this kind of linguistic territory that many of the fiercest battles rage.

Coordinated strategy?

The attacks are often not to Wikipedia’s content, but rather its community of Wikipedians.

“Some have told us that their personal information has been sprayed [released], because they have different thoughts,” Lin said.

There have also been death threats directed at Taiwanese Wikipedians. One, on the related public Wikimedia Telegram Channel, read “the policemen will enjoy your mother’s forensic report”. And elections to administrator positions on Wikipedia, who hold greater powers, have similarly become starkly divided down geopolitical lines.

Attributing online activity to states is often impossible, and there is also no direct, proven link between any of these edits and the Chinese government.

“It’s absolutely conceivable,” Tsui continued, “that people from the diaspora, patriotic Chinese, are editing these Wikipedia entries. “But to say that is to ignore the larger structural coordinated strategy the government has to manipulate these platforms.”

Whilst unattributed, the edits do happen against the backdrop where a number of states, including China, have intensified attempts to systematically manipulate online platforms. They have done so on Twitter and Facebook, and researchers around the world have warned of state-backed online propaganda targeting a range of others.

Compared with almost any other online platform, Wikipedia makes for a tempting, even obvious, target.

“I’m absolutely not surprised,” said Heather Ford, a senior lecturer in digital cultures at the University of New South Wales, whose research has focused on the political editing of Wikipedia. I’m surprised it’s taken this long actually… It is a prioritised source of facts and knowledge about the world.”

Of course, every state cares about its reputation.

“China is the second largest economy in the world and is doing what any other country in this status would seek,” said Shirley Ze Yu, a visiting senior fellow at the LSE. “Today China does owe the world a China story told by itself and from a Chinese perspective. I think it’s not only Chinese privilege, it’s really a responsibility”.

Taiwan is itself locked in a messaging war with China, with its own geopolitical points to make and many of the misconceptions may be genuine ones, at least in the eyes of the people who edit them.

So does this amount to telling China’s story, or online propaganda?

At least on Wikipedia, the answer depends on where you fall on two very different ideas about what the internet is for. There is the philosophy of open knowledge, open source, volunteer-led communities.

But it may now be confronted by another force: the growing online power of states whose geopolitical struggles to define the truth now extend onto places like Wikipedia that have grown too large, too important, for them to ignore.

* The Chinese Embassy was approached for a comment but we did not receive a reply.